Etymologically, “epiphany” in English is rather interesting; it has a primitive Indo-European root (bha, “to shine”), and means really “show forth”, or in its Greek origins to manifest the presence of a god and, in the case of the New Testament, of Christ. It also gives us that rather pleasant little word “tiffany” which was the everyday name of the feast in Norman French. The Tiffany of Art-deco lamp and jewellery fame may or may not be connected; certainly the family name goes back to the thirteenth century.

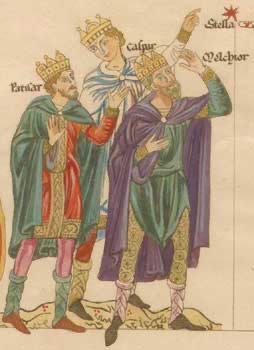

That all being said, the Christian Epiphany is – at least in the West – largely associated with the Magi, the so-called Three Kings. Of course, in fact, as I was happy to tell our young servers when they asked on Tuesday, we don’t really know the number of the magi, only the number of gifts. Indeed, Michael the Syrian, a twelfth century patriarch of Antioch, gives us a list of eleven rather Zoroastrian names. The magi were, probably, a caste of Babylonian priest-philosophers. They’re mentioned in Aristotle and elsewhere in Greek literature, sometimes positively, and sometimes negatively. We find the same thing in the New Testament: Matthew’s magi are very different from the magician Simon in the book of Acts (8:9ff). So what is going on? Here it seems to me are two responses to Christ: on the one hand the purification and Christianisation of the Magi who do homage to the infant God, and the other whose basis for belief is its usefulness as power. This latter can never have a place in genuine Christianity, although of course we see it occur and be overcome many times in the history of the Church.

This choice – between fulfilment in Christ and a collapse into paganism or materialism – always happens to each field of human knowledge or religion. It can’t be otherwise if we take seriously the totality of the claims of Christianity in respect of not only the human person, but of creation as a whole. In his novel That Hideous Strength C.S. Lewis represents this idea in the person of Merlinus, the Pendragon, and the remnant of the Logres, and the enemy, the National Institute of Coordinated Experiments. Merlinus, although a Christian, still belongs in some sense to the older, magical, order: he is willing to go “up and down, in and out” to awaken the power of land and air and water to defend Logres. The NICE on the other hand, want to acquire this power for their own means, to create as Lewis calls it, the materialist-magician. Of course, while one use of this power is at least pointing in the right direction, neither is in essence “good”. It is only, in fact, when Merlinus puts himself at the service of the Divine authorities – in the end, that means fully at the service of Christ – that his power is purified and brought into harmony with God’s creative and salvific work.

I mention all this because this blog – when I first had the idea of it years ago – was named after that idea of Logres which exists in the pages of That Hideous Strength (for anyone noticing the similarity between Logres and Lloegr which in modern Welsh is used to mean England, it’s important to note that it is a sort of trick of etymology: Logres (Lloegyr) is that happy kingdom of Arthur, in the matter of Britain, and has nothing to do with Anglo-Saxons) and the whole novel is in a sense about the purification and stripping away of those things which separate its characters from God and, really, from their own ability to be fully human.

But it’s relevant to the story of the Magi too, in as much as the temptations of power – spiritual and scientific – are always present and almost always in the same structure. It would have been easy for the Magi to feel threatened by the birth of a new divine being, entering the house of their knowledge and asking of them an entirely new way of thinking and living; it would have been natural for them to want to co-opt that power for their own advantage; or how simple to have told Herod where the child was and been rid of him, removing the danger to their own place in the world and ensuring their place – albeit negatively – in history.

Yet the Magi choose quite a different path, one which in fact means they not only prostrate themselves physically before the infant Jesus, but also spiritually and in the life of the mind. It is not a path of “greatness” in the ordinary sense, for in choosing it they must not only “return by another way” (Matt. 2:12) – in itself turning a common turn of phrase into a theological insight – but also not “return to Herod”, in other words they cannot, and do not, go back to what and who they were before their encounter with Christ. In the end it is as Eliot puts it at the end of his well-known poem:

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

There is no going back, no return to the old, however we might hanker after it or romanticise it, because the encounter with Christ – personal, cultural – is always the centre-point of histories. We might reject it, but that doesn’t mean we can ignore or forget it. The once noble Roman, or the profound wisdom of a Socrates (or Plato), or an Einstein, or that sort of terrifying power born in the imagination of an Oppenheimer, must bring their themes into the symphony of God’s creative work whose supreme and magisterial theme is Christ. If they do not, then they are ultimately emptied of meaning and either become fossils, or something worse.

Maybe this progress – which is the real kind – seems impossible. It is made through “doubts, reproaches, boredom, the unknown”, but is ultimately, as the Magi experience, a reaching towards Christ who is the north-star, the fundament of all possible humanity, the unequivocal good-will of the Father towards all people. Auden, in his For All Time: A Christmas Oratorio (1942) expresses something like this, and I close with a short passage from the section At the Manger:

Our arrogant longing to attain the tomb,

Our sullen wish to go back to the womb,

To have no past,

No future,

Is refused.

And yet without our knowledge, Love has used

our weakness as a guard and guide.

– We bless –

Our lives’ impatience,

Our lives’ laziness,

And bless each each other’s sin, exchanging here

Exceptional conceit

With average fear.

Released by Love from isolating wrong,

Let us for Love unite our various song,

Each with his gift according to his kind

Bringing this child his body and his mind.